The Human Within the Inhuman

- JotitOwl

- Dec 27, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 28, 2025

NOTE: This article will contain a few spoilers of the Imaginarium Geographica.

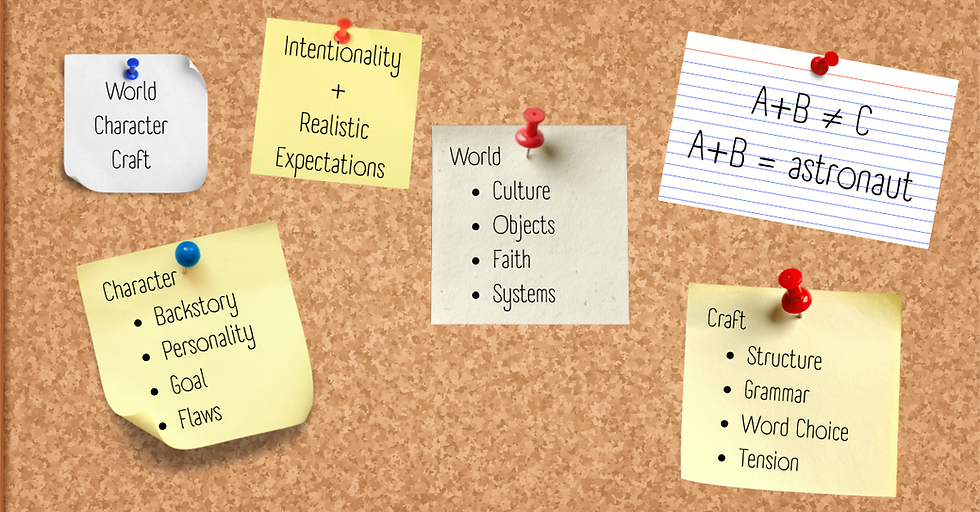

Last couple of blog posts, I've been really honing in on what realistic expectations is to me and how it applies to fantasy writing.

To recap briefly: realistic expectations are the conscious effort to bring humanity into your writing. They are the emotions, feelings, thoughts, and quiet understandings that come from shared experiences and empathetic responses. Writing with realistic expectations just means to always have that conscious thought of "how am I going to make my readers believe in this story enough to keep going."

I've also been hinting at another thing - that realistic expectations can be found in any genre of writing, including fantasy. That sounds counterintuitive, I know, but there's more truth in fantasy sometimes than we realize.

I'm so glad I get to say that without feeling weird about it. When I was growing up, fantasy wasn't loved. Still isn't in some circles. The older generations of my family still wonder what use there is in books about made up worlds. But I'm a die-hard fantasy fan. I love that worlds get to make sense even if they don't follow our rules. As if our rules were the only ones that mattered.

Let me explain.

Write What You Know

There's this book series called Here, There Be Dragons by James A. Owen. Quick premise: three young men called John, Jack, and Charles are united in Oxford after the death of John's mentor, Stellan. They are whisked away on a pretty dangerous adventure after being dubbed caretakers of the Imaginarium Geographica - a book that contains the maps of made up worlds. It's powerful. It's dangerous. There's always three caretakers. And someone dangerous is coming after them. They are guided by former caretaker of the book, Bert, who has them board his dragon boat and set sail to keep the book safe. All while, the men try fervently to deny the existence of elves, dwarves, animals that can talk, and yes, dragons. In the end, they come out of it wiser (as all protagonists do).

And that's just the first book.

What got me in the end was learning who the caretakers of the Imaginairum Geographica actually were. You'll know them, too.

John - J.R.R. Tolkien, author of the Lord of the Rings Trilogy and Middle Earth books.

Jack - C.S. "Jack" Lewis, author of The Chronicles of Narnia

Charles - Charles Williams, author of War in Heaven, Descent into Hell, All Hallows’ Eve

Bert - H.G. Wells, author of The Time Machine and War of the Worlds

Three of them part of that Oxford literary circle who called themselves The Inklings. And there's more. Every caretaker of the Imaginarium Geographica has been some kind of fantasy author, writing about the Inhuman and the unknown from lived experiences.

There's a reason I'm bringing this up and it has a lot to do with the phrase "write what you know."

I hated that phrase growing up. Write what you know. When I was in elementary school (early 2000s) this was paraded about as sage writing advice. My teachers would lob it at me left, right and center.

Never made sense. Ever. In my admittedly very concrete thought process, I thought then that circumstances I never personally experienced were off limits to me. The advice says you're only an expert in your immediate experiences, that what you know is the only thing of value to include in your stories. And so, as a ten year old child, I thought the door might be closed forever.

And then I was introduced to fantasy.

There are very few "experiences" within the fantasy realm that are "known." Riding dragons? Wielding magic? Things a writer had never and could never “know." Yet, these popular fantasy series rose to fame and their writers to world-wide popularity. Classics like C.S. Lewis' The Chronicles of Narnia, and J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings proved that stories based wholly, or near enough, in fantasy could be popular and across decades at that.

I love James A. Owen. I also privately want to believe that his books aren't just fantasy but actual biography. In that case, all I have to do is go searching for glowing portals in public parks or dragon ships in London harbors.

So, either fantasy authors are holding out on us who want to follow in their footsteps, or there's more to this advice.

What is Known and What is Real

Write what you know. I think it's been oversimplified. Like "Show, don't tell" (which I'll probably tackle in another blog post, lol). It does go hand in hand with realistic expectations, though. Think about it - what you know and what is real often go hand in hand. So why is fantasy so powerful even if it isn't real?

There are genres that already build realistic expectations into their very souls - realistic fiction, slice-of-life, romance, historical fiction, memoirs, and true crime for example - and then there are genres in which realistic expectations are not as obvious - fantasy, sci-fi, steampunk, horror, mystery, and the supernatural.

I think we forget sometimes that known and real don't just apply to reality or real life. It applies to emotion and to connection, to feelings and thoughts. It's just that fantasy adds an extra ingredient to the list - imagination.

Imagination is a powerful tool. More and more studies are showing just how important imagination is to cognitive development. In children, imagination allows exploration of concepts without the actual need to experience them. A healthy imagination is used to problem-solve and to think critically. More than that, it encourages children to channel creativity and think "What if...?" What if we add seven more? What if we say this instead? What if dragons were real?

If you want some articles to read on it, type in "imagination and cognitive development of a child" and you'll find a lot of great and interesting stuff. If you don't, you trust me at your own risk.

But I think the point still stands - imagination has a place in reality. Therefore, reality also has its place in fantasy.

The Therapist Friend

Everyone has that therapist friend (or maybe you are the therapist friend). There's a reason why we go to them. They hold a distance from the situation that we do not have and therefore have a different and newer perspective that can help us see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Fantasy is the therapist friend of the literary world. It holds emotional truths at a bit of a distance so that we can see them through fresh eyes. There's a certain safety in a fantasy world that allows us to explore deeper emotions without hurting ourselves too deeply. It places the emotional realism behind pages that we can close anytime we're feeling overwhelmed and that we can come back to when we feel ready. Those pages are the barricade. But those pages are also the things that contain the wisdom our therapist friend is trying to impart to us.

The Magician's Nephew by C.S. Lewis is a great example of the power of fantasy. On the one hand, you get an adventure story. Here's the back of the book summary (Couldn't find my copy; thank you Amazon!):

"On a daring quest to save a life, two friends are hurled into another world, where an evil sorceress seeks to enslave them. But then the lion Aslan's song weaves itself into the fabric of a new land, a land that will be known as Narnia. And in Narnia, all things are possible."

Great stuff. There's magic. An evil witch. An uncle with poor decision making skills. And two friends who overcome impossible odds. Amazing, fantastical, and written in ways that even children will get a great adventure out of it.

But even a story like that has a deep emotional truth to it. If you've read it before as a child, I'm going to challenge you to read it as an adult with a deeper understanding of what grief and living in the limbo is like when watching a family member die.

A young boy named Digory is in the process of losing his mother and is forced to live with a crazy uncle who experiments in his secret attic. His uncle essentially kidnaps him and his new friend, Polly, and sends them into an in-between place where they can dip into other worlds through pools. In one world, he feels hurt and challenged and wants control and so acts out and releases a terrible evil.

How many of us have lashed out at loved ones because we're hurting, not because they were the ones hurting us but because the pain felt better outside than in? How many of us want control over one thing in our lives and so take control where we can get it, even in the worst ways? It's why children pull fire alarms to get out of a test. It's why adults do something reckless when we're challenged. And yet does that justify our actions?

At some point in the story, Digory and Polly meet Aslan, the lion, who creates Narnia from song and breath. But the queen is also with them. The two children are set on a quest to right their wrongs and pick an apple. The queen promises a cure - one that would save his mother, if he only hands her the apple. How tempted he is to see his mother healed. But he remembers that the promises of the evil are often empty ones. Worlds destroyed if he had given into the evil queen and given her what she wanted. In the end, if he had stolen the apple to give to his mother, it would have harmed her. Only because he brought it back and gave it to someone else, relinquished control to someone who could help, did he finally have what he needed to save her.

As a child, I devoured this story three times over in a year. As an adult, I sometimes need to shut the book. The exploration of grief through the lens of a fantasy world, even knowing that the magic isn't real in the terms of our world, is a safety I need. And through it, I learn sympathy and empathy.

Fantasy doesn't fix what broke or promise cures, but it does help us sit with the emotions long enough for us to survive them. And it does it through the eyes of the Inhuman, the things that don't belong to us or to this real world, because sometimes reality is a little too much for us to be able to understand and sympathize.

Earning Hope

Okay, that was admittedly very emotional and very grief-ladden. It brought back a lot of painful memories for me, too.

But while I do think that processing emotional turmoil is definitely a plus for fantasy, it's not the only type of emotion fantasy is good at exploring. What is dark is only the beginning. Fantasy is notorious for its happy endings. That's what people are hoping for when it comes to their favorite characters. How one achieves that happy ending is generally the struggle through the darkness that authors use to fuel their plots.

Hope in itself is another concept that is safely explored through fantasy. It's funny - we don't think of hope as a dangerous topic. But it can be for those who are still stuck on the other side of their darkness. We crave hope in stories because we want to know there is another way out of this.

Genres like Dark Fantasy don't disprove that fact. Dark fantasy has it's own sort of happy ending. It's not always sunshine and rainbows, but it does end on change, and sometimes, change is all that we need to know will happen, because change brings its own kind of hope in the end.

It's the earning that makes a story real. It's not that we can't earn hope in our own world, but fantasy is uniquely promising when it comes to hope.

In realistic fiction, hope is often earned through external realism. I’m not discounting the value of those stories at all - they matter, and they resonate for a reason - but they operate within a familiar set of rules. There are systems in place, expectations we understand, and paths we recognize. We know the shape of the earned ending: a character works hard, makes mistakes, repairs a relationship, learns a lesson, and eventually opens their own business or finds stability and happiness. Hallmark movies thrive on this structure. My dad loves them. We recognize the patterns. We know the routines. That familiarity creates a sense of control. In realistic stories, we often know what we’re supposed to do - and what the characters are supposed to do - to reach the hopeful outcome.

In fantasy, realism is less concerned with external systems and more focused on emotional and internal truth. Because of that shift, fantasy helps readers process inner turmoil rather than simply observe how problems are solved on the outside. The paths forward are less predictable. The outcomes are less familiar. We don’t always know what the “right” choice looks like, or whether it will work at all. And because of that uncertainty, we are carried along for the ride. Fantasy forces us to sit with struggle as it unfolds internally, not just watch it resolve externally.

Happier emotions can be processed in the midst of pain. In fact, I'd even argue it's the most important place through which to process our happier emotions. It deepens the friendships formed through trauma and pain, stretches the foundations on which our passion and convictions lay, and lays in deep soil the growing love that when nurtured flourishes between those who have chosen each other. But they don't come without the pain.

Hope, when it finally appears, isn’t comforting because it was expected - it’s powerful because it had to be earned.

Conclusion

Fantasy is unique not because it escapes reality but because it engages with reality differently. By creating distance through the inhuman and the impossible, fantasy allows us to confront grief, fear, and hope safely. We earn those emotions honestly. What takes place in imagined worlds often tells the deepest truths about our own.

Comments