The Intentionality of Writing and Realistic Expectations

- JotitOwl

- Dec 6, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 28, 2025

Full disclaimer - I'm self-taught. I learned through an amalgamation of my public school teachers, my academic writing professors in college, YouTube videos, books on writing craft and worldbuilding, and yes, even writing-advice gurus. Not everyone can afford an MFA, and you don't really need one to learn/do.

It's another way of learning is all.

I have a Bachelor's in English, a crap-ton of novels, and a bookshelf/laptop full pages saved from different authors, storytellers, videographers, scene writers, and editors.

That's it.

Some of this advice will definitely sound like I'm pulling this shit out of thin air. Others might sound like advice from other people that I've pulled together from my research. At the end of it all is just a philosophy on writing, not a "live by the sword, die by the sword" mentality. And like any good philosophy, it has and will likely to continue to evolve and grow.

With that being said...

Writing must be intentional and deliberate

Any storyteller knows this - tucked perhaps in the deep annals of some dusty little notebook they scrawled in while listening to professors lecture or writing gurus pitch "world-changing writing advice." The desire to build a world that was other - other than ourselves, other than our world, other even than reality - was to us a siren's call from the depths of a massive ocean. We did NOT go into this lightly. We at least perused the shelves of some dive shop searching for the bare minimum of what we needed before jumping straight into that ocean. I mean, if you've never written a book before, you may not realize how utterly consuming the art is. So to go into it without a plan or care in the world sounds frankly insane. Without intentionality, we're often listless. That's not to say we always have to know where we're going (hello, pantsers!) but even those who don't have a road map at least know what they've chosen to do and are well-prepared.

See, knowing about something and doing it well are two vastly different things. You can't just know writing. You also have to be prepared to do it.

Anyone who has kids or has interacted with them for a good length of time has probably endured through this stage of childhood where impulses and intentions don't always equal positive experiences. I know when I was a child, whenever I was reminded by my parents of a rule - don't touch the stove when it's hot - I automatically responded with "I know!" And my parents? Patiently responded, "If you know it, do it!"

Let's just say my little know-it-all ass quickly learned to listen about hot burners.

I see the same thing in other children within that precarious pre-pre-teen era where they want to please and be good kids but also want to be themselves and don't often know how to handle those big emotions. They often get stuck between industry and individuality. They tell me, after learning a skill or being reminded of a rule, they already know. And I whip out the same phrase my parents used: "If you know it, do it."

Sometimes things are that simple. Following the rules, being kind, and knowing how to subtract across zeroes or use a formula to figure out area. There are tried and true steps and procedures. But sometimes things aren't that simple. Sometimes they're big emotions and uncertainty. I know writing is rarely that simple (even though sometimes I wish it were as simple as snapping my fingers and making the worlds in my head appear on page). Everyone "knows" how to do it. Not everyone can do it well.

Storytelling has both straight lines and curved lines, bends and angles. Just think geometry for writing, and you'll get a close proximity.

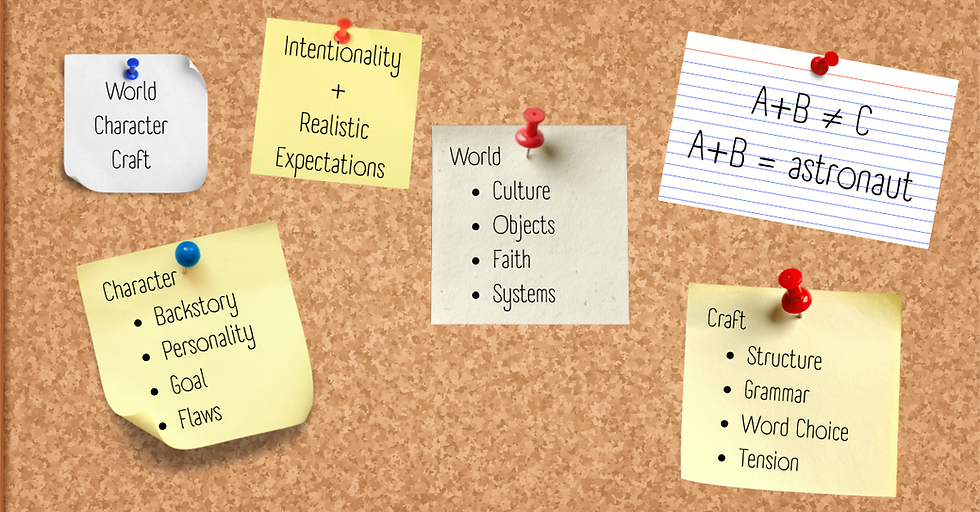

For me, I've found that the best writing advice comes from people who admit fully that this art isn't as straight forward as formulas. A+B ≠ C. Sometimes A+B = astronaut. It depends on the person. I'll not say this is solid "do it my way and you'll be on your way to being an amazing author."

Ha!

No.

But I will say this approach - this philosophy - has worked for me. I don't recommend it. I'm fairly certain my brain has it's own reality setting. Still, in case anyone's interested in the depths of my crazy, feel free to keep going.

World, Characters, Craft

Storytellers often find themselves caught up in a tenuous balance between the characters and the world they occupy. Leaning too far into world building results in flat characters and poorly executed growth arcs. Likewise, too much character work results in a lifeless, unanchored ghost world.

Let's put it this way. The characters should be fully realized with thoughts, feelings, emotions, strengths, and flaws. They breathe life into the world through their experience because no two characters will perceive the same situation in the same way. But the story is more than just the characters. It's land and culture, other people and creatures, items and systems. These things inform the world in which characters grow, learn, change, and go on their adventures. Without a world for them to live in, what's the point of it all?

I don't know about you, but without a world to share my things, I'd never have become a writer.

Think of it like the world of a video game. Players rave about more than just the plot and character backstory.

"Check out the scenery! The graphics are crazy!" they might say standing on a cliff and overlooking an in-game sunset.

"This NPC's backstory is deeply suspicious..." they might say about the average milk seller on the corner.

"I've spent hours hunting down this weapon. It's supposed to boost all your stats by five!" others say after an adventure.

You get a balance of both. Without plot and character, you have a world with nothing to do. But without NPCs, objects, items, systems, cultures, and rules, the player - or in the case of a novel, the character - may lack motivation or the means by which they are able to achieve their goals. Then there's no story.

And don't forget craft! Craft is the bridge between the two entities, the one thing that makes it possible for readers to learn about both character and world. As storytellers, we hone our craft as much as possible to make it interesting and important. We cannot ignore the power of a well-crafted sentence. Consider structure, tension, conflict, phrasing, and word choice as the missing links that build said balance between the characters and the world, making the foundation strong.

There's honestly one thing that really shows off what all three can do when balanced well.

Delving into Dungeons and Dragons

Dungeons and Dragons (D&D).

No, I'm serious. You want one of the best examples of world, character, and craft balance, check it out.

D&D, if you haven't heard of it, is a table-top role playing game. The quick of it? Adventure packed hours of campaign nonsense, insanity, and bad decisions. The long of it? It's absolutely gorgeous.

Dungeon/Game Masters create immersive worlds with structure and systems that pose various problems tailored to the players' motivations. They craft NPC characters with specific roles and purposes that directly influence the players' perception, and provide items or paths to items that players can acquire - items that may help or may hinder. Their structures and systems resist character influence by providing consequences for their actions, thus creating a push-pull system that immediately plunges players deep into the fictional world.

The players themselves create the characters - ones who live, breathe, and hurt like real people in this world. Their choices lend to their overall experiences of success, failure, heartbreak, and even death. They eventually shape the world they've chosen to submerge themselves in and give weight to repercussions that ripple outwards.

And then there's craft. I'm not gonna lie to you - my experience with D&D is through YouTube and Reddit stories unfortunately. I don't have a group of friends I could hold captive for hours on end in a story world. But if you've never watched Dimension 20 or Critical Role or any of the DMs like Brennan Lee Mulligan, Aabria Iyengar, and Matthew Mercer, I pity you for you have missed out on masters of craft.

DMs need strong control of game mechanics - that's tone, pacing, and plot devices. But they also know craft like word choice and phrasing to make things interesting. And have you ever seen how quickly they can turn a phrase or whip out a monologue? I don't care if it's pre-planned or what. The absolute skill one needs to turn a phrase like that. There's also that stereotype - which by the way would never have become a stereotype if it weren't true many times - of players making diabolically stupid decisions and ruining a DM's previously planned campaign either by dying or by becoming chaos incarnate. If you've never had to make those kinds of split second decisions on where to take the story next because all of your prepared content is suddenly not enough, then you don't realize the skill that takes.

I'm in awe.

This phenomenon - this immersivity of one who experiences a story - is only possible through the careful balance of world, character, and craft and a healthy dose of intentionality with all three.

And just so we're clear - you need both. This process is what I like to call the inclusion of realistic expectations.

Realistic Expectations

Realistic expectations shape the way we approach story. While world building, character building, and craft work are essential to the creation of a good story, intentionality is essential to its success. Altogether, it's a rather precarious balance storytellers seek to design. Like an architect, a storyteller must look at all the angles. Height, foundation, and even weather can affect the materials and location they choose to build their structures. Storytellers should approach a story with the same care.

The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, The Witcher series by Andrzej Sapkowski including both the books and the game series, and the Marvel Cinematic Universe (debatably only the earlier phases, though; I'm still a little leery about the middle there, but some of the new stuff is good) have withstood the test of time in part because they intentionally chose good storytelling techniques that allowed both their worlds and their characters to not just shine but build legacies.

These aren't new beliefs. I'm not the first to spit-fire this. Terminology varies. I doubt I even came up with the term "realistic expectations" on my own. But man do I think it works.

Successful authors, screenwriters, film directors, playwrights, comic artists, writing coaches, decent editors, game developers, and avid consumers of stories in various forms are all familiar with the practice of using realistic expectations.

In fact, the audience is usually the one to demand it.

There's several authors who I think also back me up here.

Shawn Coyne talks the everyday terms of motivation, goals, and consequence grounded in internal logic.

Jonathan Gottschall talks about "a universal grammar," a deeply psychological pattern found in both the "skeletal structure" of a story as well as what he deems the "flesh."

Sandra Gerth gives great advice on how to use arguably the greatest - and most poorly explained - writing advice of "show, don't tell."

Jeff Vandermeer describes "well-realized settings [that] exhibit a range of particular characteristics."

Douglas Glover writes about "static structures that give illusions of life."

Joseph Campbell's concept ties deeply to that of the "hero=path" experience that spirals back to internal revelations.

Will Storr discusses the science behind storytelling.

Each of these authors describes a balance between those things we've been talking about since the beginning. If you want to check them out, there will be a list of books at the end of this that I've used to help develop both my writing philosophy and my skills as an author and storyteller. I've synthesized what notes I've taken and what things I've read to form this idea of realistic expectations.

The synthesizing of these definitions into my personal writing philosophy has taken the advice of not just writers but also historians, psychologists, literary analysts, scientists, teachers, and one very clever FBI agent whose book I picked up by happy accident - one I’ve never regretted. It was largely developed over many years of trial, error, pride, stubbornness, and learned humility.

Realistic expectations tend towards only one conclusion in my mind, and it’s this conclusion that will guide the path, every path, forward: The world does not revolve around the characters. Rather the characters interact with and influence the world - and the world is allowed to push back.

Conclusion

That's my philosophy.

The world does not revolve around the characters. Rather the characters interact with and influence the world - and the world is allowed to push back.

That's what drives every story I plan, every world I create, every character I discover, every plot I invent. It works. Most of the time. And for some of the time that's when instincts come in. Like I said earlier - instincts are still essential.

But that's a post for another time.

Authors and the Books I've Referenced

Wonderbook by Jeff Vandermeer

Honestly one of the best "writing advice" books I've ever read. It's so in depth and absolutely brilliant in the way he explains things. And he's an author of fantasy himself. I like to delve into craft and worldbuilding on the regular and this was one of the best research finds.

Show, Don't Tell by Sandra Gerth

Great craft book, excellent advice, and amazing examples of what "show, don't tell" means. I've learned a lot.

This is the book from that clever FBI agent I mentioned. While he mostly meant it for reading body language, I used it for showcasing emotion shown not told. Paired with Gerth, it makes an excellent guide. Never say that non-writing reference books aren't useful! (Yes, I've heard that before). He's got others, too, but I haven't had a chance to read those yet. There might be several body language reading books out there, but he makes the reading and research part fun.

The Story Grid by Shawn Coyne

I'm still making my way through this one. I agree with a lot and some I'm trying to decide whether I agree or not. Regardless, there's some really good information here.

The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make us Human by Jonathan Gottschall

Absolutely fascinating piece on the link between psychology and storytelling. It's pretty much the best delve into reader expectations and how we can use those expectations to further make our stories unforgettable. I'm in awe of his ability to write - he definitely puts what he preaches to practice.

The Science of Storytelling by Will Storr

Also a great read. Psychology and science come together to write a good story. Like Gottschall, Storr also writes about how we can use what readers expect - realistic expectations; what we know they want - to tell a great story.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell

Haven't read it all the way through, but the hero's journey is something I studied extensively during one class in college when getting my first degree. I've not forgotten what I learned and that was nearly ten years ago. I'm not gonna lie - I was bored most of the time when reading and it was a little dense. Honestly, Campbell is lucky I had an amazing professor who made it come to life through his own passion.

Attack of the Copula Spiders by Douglas Glover

This one's not really a writing advice book, nor is it written for the fiction author in mind. Glover wrote this as a guide for the academic writer to close reading. However, while close reading is technically an academic skill, a storyteller can use his advice to really understand how good writing works and use it to study your favorite authors. The grammatical knowledge this man wields is amazing, and I still use some of his stuff unconsciously. Also recommended by an amazing and passionate professor.

Comments